Author Archives: Lydia Leong

Trialing a lot of cloud IaaS providers

I’ve just finished writing the forthcoming Public Cloud IaaS Magic Quadrant (except for some anticipated tweaks when particular providers come back with answers to some questions), which has twenty providers. Although Gartner normally doesn’t do hands-on evaluations, this MQ was an exception, because the easiest way to find out if a given service can do X, was generally to get an account, and attempt to do X. Asking the vendor sometimes requires a bunch of back-and-forth, especially if they don’t do X but and are weaseling their reply, forcing you to ask a set of increasingly narrow, specific questions until you get a clear answer. Also, I did not want to constantly bombard the vendors with questions, since, come MQ time, it tends to result in a firedrill whether or not you intended the question as urgent or even particularly important. (I apologize for the fact that I ended up bombarding many vendors with questions, anyway.)

I’ve used cloud services before, of course, and I am a paying customer of two cloud IaaS providers and a hosting provider, for my personal hobbies. But there’s nothing quite like a blitzkrieg through this many providers all at once. (And I’m not quite done, because some providers without online sign-up are still getting back to me on getting a trial account.)

In the course of doing this, I have had some great experiences, some mediocre experiences, and some “you really sell this and people buy it?” experiences. I have online chatted with support folks for basic questions not covered in the documentation (like “if I stop this VM, does it stop billing me, or not?” which varies from provider to provider). I have filed numerous support tickets (for genuine issues, not for evaluation purposes). I have filed multiple bug reports. I have read documentation (sometimes scanty to non-existent). I have clicked around interfaces, and I have actually used the APIs (working in Python, and in one case, without using a library like libcloud); I have probably weirded out some vendors by doing these things at 2 am, although follow-the-sun support has been intriguing. Those of you who follow me on Twitter (@cloudpundit) have gotten little glimpses of some of these things.

Ironically, I have tried to not let these trials unduly influence my MQ evaluations, except to the extent that these things are indisputably factual — features, availability of documentation, etc. But I have taken away strong impressions about ease of use, even for just the basic task of provisioning and de-provisioning a virtual machine. There is phenomenal variation in ease of use, and many providers could really use the services of a usability expert.

Any number of these providers have made weird, seemingly boneheaded decisions in their UI or service design, for which there’s no penalty to anything in MQ scoring, but did occasionally make me stare and go, “Seriously?”

I’m reluctant to publicly call out vendors for this stuff, so I’ll pick just one example from a vendor that has open online sign-up, where it’s not a private issue that hasn’t been raised on a community forum, and they’re not the sort of vendor (I hope) to make angry calls to Gartner’s Ombudsman demanding that I take this post down. (Dear OpSource folks: Think of this as tough love, and I hope Dimension Data analyst relations doesn’t have conniptions.)

So, consider: OpSource has pre-built VMs, that come with a set amount of compute and RAM, bundled with an OS. Great. Except that you can’t alter a bundle at the time of provisioning. So, say, if I want their Ubuntu image, it comes only in a 2 CPU core config. If I want only 1 core, I have to provision that image, wait for the provision to finish, go in and edit the VM config to reduce it to 1 core, and then wait for it to restart. After I go through that song and dance once, I can clone the config… but it boggles the mind why I can’t get the config I want from the start. I’m sure there’s a good technical reason, but the provider’s job is to mask such things from the user.

The experience has also caused me to wholly revise my opinion of vCloud Director as a self-service tool for the average goomba who wants a VM. I’d always seen vCD as a demo being given by experts, where it looked like despite the pile of complex functionality, it was easy enough to use. The key thing is that the service catalogs were always pre-populated in those demos. If you’re starting from the bare vCD install that a vCloud Powered provider is going to give you, you face a daunting task. Complexity is necessary for that level of fine-grained functionality, but it’s software that is in desperate need of pre-configuration from the service provider, and quite possibly an overlay interface for Joe Average Developer.

Now we’ll see if my bank freezes my credit card for possible fraud, when I’m hit with a dozen couple-of-cents-to-a-few-dollar charges come the billing cycle — I used my personal credit card for this, not my corporate card, since Gartner doesn’t actually reimburse for this kind of work. Ironically, once I spent a bunch of time on these sites, Google and the other online ad networks have started displaying ads that consist of nothing but cloud providers, including “click here for a free trial” or “$50 credit” or whatever, but of course you can’t apply those to existing accounts, which makes every little, “hey, you’ve spent another ten cents provisioning and de-provisioning this VM” charge which I’m noting in the back of my head now, into something which will probably annoy me in aggregate come the billing cycle.

Some things, you just can’t know until you try it yourself.

Results of Symposium workshop on Amazon

I promised the attendees at my Gartner Symposium workshop, called “Using Amazon Web Services“, that I would post the notes from the session, so here they are — with some context for public consumption.

A workshop is a structured, facilitated discussions that are designed to assist participants in working through a problem, coming up with best practices, etc. This one had thirty people, all from IT organizations that were either using Amazon or planning to use Amazon.

Because I didn’t know what level of experience with Amazon the workshop attendees would have, I actually prepared two workshops in advance. One of them was a highly structured work-through of preparing to use Amazon in a more formal way (i.e., not a single developer with a credit card or the like), and the other was a facilitated sharing of challenges and best practices amongst current adopters. As the room skewed heavily towards people who already had a deployment well under way, this workshop focused on the latter.

I started the workshop with introductions — people, companies, current use cases. Then, I asked attendees to share their use cases in more details in their smaller working groups. This turned into a set of active discussions that I allowed extra time for, before I asked each of the group to make a list of their most significant challenges in adopting/using Amazon, and their solutions if any. Throughout, I circulated the room, listening and, rarely, commenting. Each group then shared their findings, and I offered some commentary and then did an open Q&A (with some more participant sharing of their answers to questions).

Broadly, I would say that we had three types of people in the room. We had folks from the public sector and education, who were at a relatively early stage in adoption; we had people who were test/dev oriented but in a significant way (i.e., formal adoption, not a handful of developers doing their thang); and we had people who were more e-business oriented (including people from net-native businesses like SaaS, as well as traditional businesses with a hosting type of need), although that could be test/dev or production. Most of the people were mid-level IT management with direct responsibility for the Amazon services.

Some key observations:

Dealing with the financial aspects of moving to the cloud is hard. Understanding the return on investment, accurately estimating costs in advance, comparing costs to internal costs, and understanding the details of billing were common challenges of the participants. Moreover, it raises the issue of “is capital king or is expense king?” Although the broader industry is constantly talking about how people are trying to move to expense rather than capital, workshop participants frequently asserted that it was easier for them to get capital than to up their recurring expenses. (As a side note, I have found that to be a frequent assertion in both inquiry and conference 1-on-1s.) Finally, user management, cost control, and turning resources on/off appropriately were problematic in the financial context.

Move low-risk workloads first. The workshop participants generally assessed Amazon as being suitable only to test/dev, non-mission-critical workloads, and things that had specifically been designed with Amazon’s characteristics in mind. Participants recommended a risk profile of apps, and moving low-risk apps first. They also saw their security organizations as being a barrier to adoption. Many had issues with their Legal departments either trying to prevent use of services or causing issues in the contracting process (what Amazon calls an Enterprise Agreement); participants recommended not involving Legal until after adopting the service.

Performance is a problem. Performance was cited as a frequent issue, especially storage performance, which participants noted was unsuitable to their production applications, and one participant made the key point that many test/dev situations also require highly performant storage (something he had first discovered when his ILM strategy placed test/dev storage at a lower more commodity tier and it impacted his developers).

Know what your SLA isn’t. Amazon’s limited SLAs were cited as an issue, particularly the mismatch in what many users thought the SLA was versus what it actually was, and what it’s actually turned out to be in practice (given Amazon’s outages this year). Participants also stressed business continuity planning in this context.

Integration is a challenge. Participants noted that going to test/dev in the cloud, while maintaining production in an internal data center, splits the software development lifecycle across data centers. This can be overcome to some degree with the appropriate tools, but still creates challenges and sometimes outright problems. Also, because speed of deployment is such a driving factor to go to the cloud, there is a resulting fragmentation of solutions. A service catalog would help some of these issues.

Data management can be a challenge. Participants were worried about regulatory compliance and the “where is my data?” question. Inexperienced participants were often not aware that non-S3 data is generally local to an availability zone. But even beyond that, there’s the question of what data is being put where by the cloud users. Participants with larger amounts of data also faced challenges in moving data in and out of the cloud.

Amazon isn’t the right provider for all workloads in the cloud. Several workshop participants used other cloud IaaS providers in addition to Amazon, for a variety of other reasons — greater ease of use for users who didn’t need complex things, enterprise-grade availability and performance, better manageability, security capabilities, and so forth.

I have conducted cloud workshops and what Gartner calls analyst/user roundtables at a bunch of our conferences now, and it’s always interesting what the different audiences think about, and how much it’s evolving over time. Compared to last year’s Symposium, the state of the art of Amazon adoption amongst conference attendees has clearly advanced hugely.

Gartner Symposium this week

I am at Gartner Symposium in Orlando this week, and would happy to meet and greet anyone who feels like doing so.

I am conducting a workshop on Thursday, at 11 am in Salon 7 in Yacht and Beach, called “Using Amazon Web Services“. (The workshop is full, but it’s always possible there may be no-shows if you’re trying to get in.) This workshop is targeted at attendees who are currently AWS customers, or who are currently evaluating AWS.

Gartner Invest clients, I’ll be at the Monday night event, and willing to chatter about anything (CDNs, especially Akamai, seem to be the hot topic, but I’m getting a fair chunk of questions about Rackspace and Equinix).

I hope to blog about some trends on my one-on-one interactions and other conversations at the conference, as we go through the week.

What does the future of the data center look like to you?

Earlier this year, I was part of a team at Gartner that took a futuristic view of the data center, in a scenario-planning exercise. The results of that work have been published as The Future of the Data Center Market: Four Scenarios for Strategic Planning (Gartner clients only). My blog entries today are by my colleague, project leader Joe Skorupa, and provide a glimpse into this research. See the introduction for more information.

The Scenarios

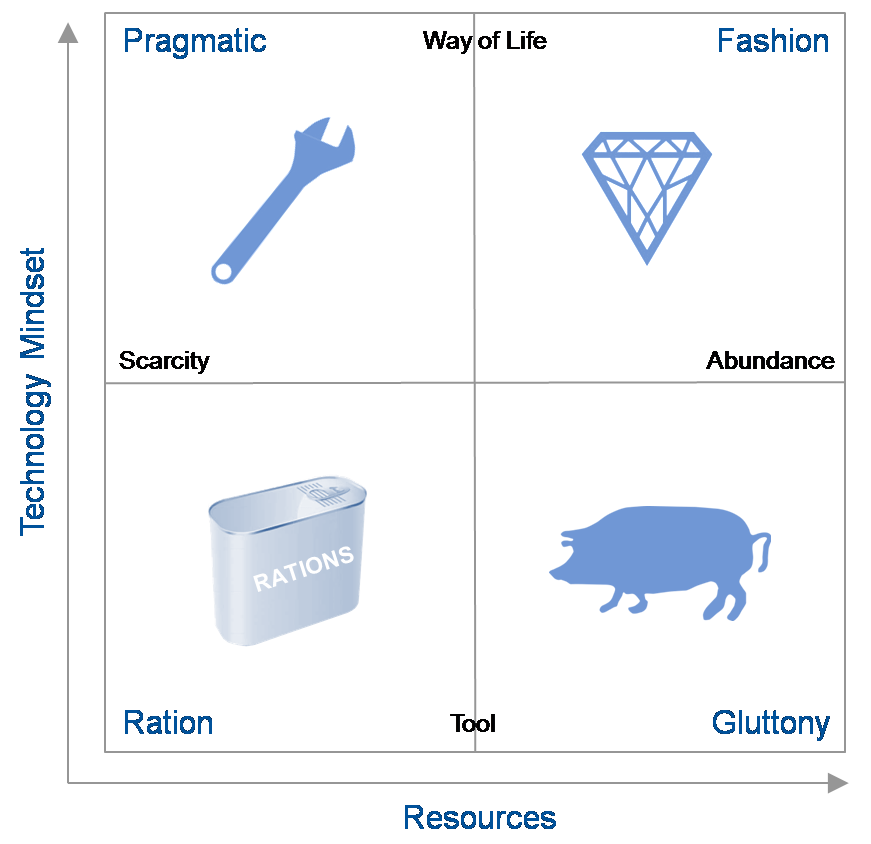

Scenarios are defined by the 4 quadrants that result from the intersection of the axes of uncertainty. In defining our scenarios we deliberately did not choose technology-related axes because they were too limiting and because larger macro forces were potentially more disruptive.

We focused on exploring how the different external factors outlined by the two axes would affect the environment into which companies would provide the products and services. Note that these external macro forces do contain technological elements.

The vertical axis describes the role and relevance of technology in the minds of the consumers and providers of technology while the horizontal axis describes availability of resources – human capital (workers with the right skill set), financial capital (investments in hardware, software, facilities or internal development) or natural resources, particularly energy — to provide IT. The resulting quadrants describe widely divergent possible futures.

- The “Tech Ration” Scenario

- This scenario describes the world in 2021 that is characterized by severely limited economic, energy, skill and technological resources needed to get the job done. People view technology as they used to think of the telephone – as a tool for a given purpose. After a decade of economic decline, wars, increasingly scarce resources and protectionist government reactions, most businesses are survival-focused.

Key Question: What would be the impact of a closed-down, localized view of the world on your strategic plans?

- The “Tech Pragmatic” Scenario

- This scenario presents a similar world of limited resources but where people are highly engaged with IT and it forms a key role in their lifestyles. Social networks and communities evolved over the decade into sources of innovation, application development and services. IT plays a major role in coordinating and orchestrating the ever-changing landscape of technology and services.

Key Question: Will your strategy be able to cope with a world of limited resources but the need for agility to meet user demands?

- The “Tech Fashion” Scenario

- This scenario continues the theme where the digital natives’ perspectives have evolved to where technology is an integral part of people’s lives. The decade preceding 2021 saw a social-media-led peace, a return to economic growth, and a flourishing of technology from citizen innovators. It is a world of largely unconstrained resources and limited government. Businesses rely on technology to maximize their opportunities. However, consumers demand the latest technology and expect it to be effective.

Key Question: How will a future where the typical IT consumer owns multiple devices and expects to access any application from every one of their devices affect your strategic planning?

- The “Tech Gluttony” Scenario

- This scenario continues in 2021 with unconstrained resources where people view technology as providing separate tools for a given purpose. Organizations developed situation-specific products and applications. Users and consumers view their technology tools as limited life one-offs. IT budgets become focused on integrating a constantly shifting landscape of tools.

Key Question: Does a world of excessive numbers of technological tools from myriad suppliers change your strategic planning?

The four scenario stories each depicts the journey to and a description of a plausible 2021 world. Of course the real future is likely to be a blend of two or more of the scenarions. To gain maximum value, you should treat each story as a history and description of the world as it is. To gain maximum benefit suspend disbelief, immerse yourself in the story, and take time to reflect on the implications for your business and enter into discussion on what plans would be most beneficial as the future unfolds.

ObPlug: Of course, Gartner analysts are available to assist in deriving specific implications for your business and formulating appropriate plans.

Introduction to the Future of the Data Center Market

Earlier this year, I was part of a team at Gartner that took a futuristic view of the data center, in a scenario-planning exercise. The results of that work have been published as The Future of the Data Center Market: Four Scenarios for Strategic Planning (Gartner clients only). My blog entries today are by my colleague, project leader Joe Skorupa, and provide a glimpse into this research.

Introduction

As a data center focused provider, how do you formulate strategic plans when the pace and breadth of change makes the future increasingly uncertain? Historical trends and incremental extrapolations may provide guidance for the next few years, but these approaches rarely account for disruptive change. Many Gartner clients that sell into the data center requested help formulating long-range strategic plans that embrace uncertainty. To assist our clients, a team of 15 Gartner from across a wide range of IT disciplines employed the scenario-based planning process to develop research about the future of the data center market. Unlike typical Gartner research, we did not focus on 12-18 month actionable advice; we focused on potential market developments/disruptions in the 2016-2021 timeframe. As a result its primary audience is C-level executives that their staffs that are responsible for long-term strategic planning. Product line managers and competitive analysts may also find this work useful.

Scenario-based planning was adopted by the US Department of Defense in the 1960s and the formal scenario-based planning framework was developed at Royal Dutch Shell in the 1970s. It has been applied to many organizations, from government entities to private companies, around the world to identify major disruptors that could impact an organization’s ability to maintain or gain competitive advantage. For this effort we used the process to identify and assess major changes in social, technological, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) environments.

These scenarios are told as stories and are not meant to be predictive and the actual future will be some subset of one or more of the stories. However, they provide a basis for deriving company-specific implications and developing a strategy to enable your company to move forward and adapt to uncertainty as the future unfolds. Exploring alternative future scenarios that are created by such major changes should lead to the discovery of potential opportunities in the market or to ensure the viability of current business models that may be critical to meeting future challenges.

To anchor the research, we focused on the following question (the Focal Issue) and its corollary:

Focal Issue: With rapidly changing end-user IT/services needs and requirements, what will be the role of the data center in 2021 and how will this affect my company’s competitiveness?

Corollary: How will the role of the data center affect the companies that sell products or services into this market?

The next post describes the scenarios themselves.

The Global Internet Speedup Initiative

The rather prosaically-named, if accurately and precisely named, IETF draft specification, “Client Subnet in DNS Requests” (“edns-client-subnet”), has gotten some breathless marketing spin as the Global Internet Speedup Inititative.

I blogged about this about a year and a half ago: “Google’s DNS protocol extension and CDNs“. See that post for a deeper analysis. (I also previously blogged about the problem with using DNS as the CDN vantage point.)

My opinion on this hasn’t changed. In the intervening time, various DNS service providers and CDN providers have contributed to the draft, and the end result seems to be pretty reasonable. The extension solves a common problem for the CDNs — returning appropriately close CDN servers to an end-user who is using a DNS resolver that’s not close to his own location (common for users on some ISP networks, along with those who use resolvers from OpenDNS, Neustar, etc., and potentially for some users in enterprise networks).

But I am impressed with the amount of hype that the vendors involved have managed to generate about a fiddly little technical detail that ordinary users have probably never thought about and shouldn’t ever really need to think about.

VMware vCloud Global Connect and commoditization

At VMworld, VMware has announced vCloud Global Connect, a federation between vCloud Datacenter Provider partners.

My colleague Kyle Hilgendorf has written a good analysis, but I wanted to offer a few thoughts on this as well.

The initial partners for the announcement are Bluelock (US, based in Indianapolis), SingTel (Singapore), and SoftBank Telecom (Japan). Notably, these vendors are landlocked, so to speak — they have deployments only within their home countries, and who probably will not expand significantly beyond their home territories. Consequently, they’re not able to compete for customers who want multi-region deployments but one throat to choke. (Broadly, there are still an insufficient number of high-quality cloud providers who have multi-region deployments.)

These providers are relatively heavyweight — their typical customers are organizations which are going through a formal sourcing process in order to procure infrastructure, and are highly concerned about security, availability, performance, and alignment with enterprise IT. I expect that anyone who chooses federation with Global Connect is going to apply intense scrutiny to the extension provider, as well. At least because the vCloud Datacenter architecture is to some extent proscriptive, and has relatively high requirements, in theory all federation providers should pass the buyer’s most basic “is this cloud provider architected in a reasonable fashion” checks.

However, I think customers will probably strongly prefer to work with a truly global provider if they need truly global infrastructure (as opposed to simply trying to globally source infrastructure that will be used in unique ways within each region) — and those with specific regional needs are probably going to continue to buy from regional (or local) providers, especially given how fragmented cloud IaaS sourcing frequently is.

It’s an important technical capability for VMware to demonstrate, though, since, implicitly, being able to do this between providers also means that it should be possible to move workloads between internal vClouds and external vClouds, and to disaster-recover between providers.

Importantly, the providers chosen for this launch are also providers who are not especially worried about being commoditized. Their margin is really made on the value-added services, especially managed services, and not so much from just providing compute cycles. Each of them probably gains more from being able to address global customer needs, than they lose from allowing their infrastructure to be used by other providers in this fashion.

I do believe that the core IaaS functionality will be commoditized over time, just like the server market has become commoditized. I believe, however, that IaaS providers will still be able to differentiate — it’ll just be a differentiation based on the stuff on top, not the IaaS platform itself.

In the early years of the market, there is significant difference in features/functionality between IaaS providers (and how that relates to cost), but the roadmaps are largely convergent over the next few years. Just like hosters don’t depend on having special server hardware in order to differentiate from one another, cloud IaaS providers eventually won’t depend on having a differentiated base infrastructure layer — the value will primarily come higher up the stack.

That’s not the say that there won’t still be difference in the quality of the underlying IaaS platforms, and some providers will manage costs better than others. And the jury’s still out on whether providers who build their own intellectual property at the IaaS platform layer, vs. buying into vCloud (or Cloud.com, some future OpenStack-based stack, or one of many other “cloud stacks”), will generate greater long-term value.

(For further perspective on commoditization, see an old blog post of mine.)

Recent research notes

This is just a quick call-out to draw your attention to the research that I’ve published recently.

- Do You Have a Business Case for a Top-Level Domain?

- I blogged previously on this topic, and this research note, done with my colleague Ray Valdes (whose coverage includes online user experience), dives deeply into consideration of the uses of gTLDs, the impact of gTLDs, the shifting landscape of how users find websites, and other things of interest to anyone considering a gTLD or preparing a business case for one.

- How to Deliver Video to Dispersed Users Without Upgrading Your Network

- Many organizations that are trying to deliver video to a lot of users think that they should use a traditional CDN. That’s not necessarily the right solution. This research note examines the range of solutions, divided by the delivery targets — Internet users outside your organization, your own employees at remote sites, Internet VPN users, and mixed-usage scenarios.

- How to Accelerate Internet Websites and Applications

- There are a range of techniques that can be used for acceleration — netwok optimization, front-end optimization (sometimes called Web content optimization or Web performance optimization), and caching — that can be delivered as appliances or services. This research note looks at selecting the right solution, and combining solutions, to maximize performance within your available budget.

(These notes are for Gartner clients only, sorry.)

What makes Akamai sticky?

There’s one thing in particular that tends to make Akamai customers “sticky” — the amount the customer uses professional services. The more professional services a customer consumes from Akamai, the less likely it is they’ll ever switch CDNs. In short: The more of a pain it’s been for them to integrate with Akamai’s CDN (usually due to the customer having a complex site that violates best practices related to content cacheability), and the more they have to use recurring professional services every time they update their site, the less likely it is that they’re going to move to another CDN. That’s for two reasons — one, because it’s difficult and expensive to do the up-front work to get the site onto another CDN, and two, because most other CDNs don’t like to do extensive professional services on a recurring basis. That makes the use of professional services a double-edged sword, since it’s not really a business with great margins, and you’re vulnerable if the customer eventually goes and builds a site that isn’t a great big hairy mess.

But there’s one Akamai product (delivered as a value-added additional service) that’s currently sufficiently compelling that customers and prospects who want it, won’t consider any other CDN that can’t offer the same. (And since it’s currently unique to Akamai, that means no competition, always a boon in a market where pricing is daily warfare.) I’m suddenly seeing it frequently quoted, which makes it likely that it’s a significant sales push, though it’s not a brand-new product. It’s a very effective attach.

Can you guess what it is?

(You may feel free to speculate on my blog, but if you want the answer, and you’re a Gartner client, make an inquiry request through the usual means.)

OpenStack, community, and commercialization

I wrote, the other day, about Citrix buying Cloud.com, and I realized I forgot to make an important point about OpenStack versus the various commercial vendors vying for the cloud-building market; it’s worthy of a post on its own.

OpenStack is designed by the community, which is to say that it’s largely designed by committee, with some leadership that represents, at least in theory, the interests of the community and has some kind of coherent plan in mind. It is implemented by the community, which means that people who want to contribute simply do so. If you want something in OpenStack, you can write it and hope that your patches are included, but there’s no guarantee. If the community decides something should be included in OpenStack, they need some committers to agree to actually write it, and hope that they implement it well and do it in some kind of reasonable timeframe.

This is not the way that one normally deals with software vendors, of course. If you’re a potentially large customer and you’d like to use Product X but it doesn’t contain Feature Y that’s really important to you, you can normally say to the vendor, “I will buy X if you had Y within Z timeframe,” and you can even write that into your contract (usually witholding payment and/or preventing the vendor from recognizing the revenue until they do it).

But if you’re a potentially large customer that would happily adopt OpenStack if it just had Feature Y, you have miminal recourse. You probably don’t actually want to write Feature Y yourself, and even if you did, you would have no guarantee that you wouldn’t be maintaining a fork of the code; ditto if you paid some commercial entity (like one of the various ventures that do OpenStack consulting). You could try getting Feature Y through the community process, but that doesn’t really operate on the timeframe of business, nor have any guarantees that it’ll be successful, and also requires you to engage with the community in a way that you may have no interest in doing. And even if you do get it into the general design, you have no control over implementation timeframe. So that’s not really doable for a business that would like to work with a schedule.

There are a growing number of OpenStack startups that aim to offer commercial distributions with proprietary features on top of the community OpenStack core, including Nebula and Piston (by Chris Kemp and Joshua McKenty, respectively, and funded by Kleiner Perkins and Hummer Winblad, respectively, two VCs who usually don’t make dumb bets). Commercial entities, of course, can deal with this “I need to respond to customer needs more promptly than the open source community can manage” requirement.

There are many, many entitities, globally, telling us that they want to offer a commercial OpenStack distribution. Most of these are not significant forks per se (although some plan to fork entirely), but rather plans to pick a particular version of the open source codebase and work from there, in order to try to achieve code stability as well as add whatever proprietary features are their secret source. Over time, that can easily accrete into a fork, especially because the proprietary stuff can very easily clash with whatever becomes part of OpenStack’s own core, given how early OpenStack is in its evolution.

Importantly, OpenStack flavors are probably not going to be like Linux distributions. Linux distributions differ mostly in which package manager they use, what packages are installed by default, and the desktop environment config out of the box — almost cosmetic differences, although there can be non-cosmetic ones (such as when things like virtualization technologies were supported). Successful OpenStack commercial ventures need to provide significant value-add and complete solutions, which, especially in the near term when OpenStack is still a fledgling immature project, will result in a fragmentation of what features can be expected out of a cloud running OpenStack, and possibly significant differences in the implementation of critical underlying functionality.

I predict most service providers will pick commercial software, whether in the form of VMware, Cloud.com, or some commercial distribution of OpenStack. Ditto most businesses making use of cloud stack software to do something significant. But the commercial landscape of OpenStack may turn out to be confusing and crowded.