Category Archives: Industry

How not to use a Magic Quadrant

The Web hosting Magic Quadrant is currently in editing, the culmination of a six-month process (despite my strenuous efforts to keep it to four months). Many, many client conversations, reference calls, and vendor discussions later, we arrive at the demonstration of a constant challenge: the user tendency to misinterpret the Magic Quadrant, and the correlating vendor tendency to become obsessive about which quadrant they’re placed in.

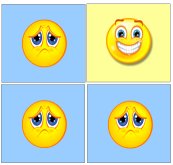

Even though Gartner has an extensive explanation of the Magic Quadrant methodology on our website, vendors and users alike tend to oversimplify what it means. So a complex methodology ends up translating down to something like this:

But the MQ isn’t intended to be used this way. Just because a vendor isn’t listed as a Leader doesn’t mean that they suck. It doesn’t mean that they don’t have enterprise clients, that those clients don’t like them, that their product sucks, that they don’t routinely beat out Leaders for business, or, most importantly, that we wouldn’t recommend them or that you shouldn’t use them.

The MQ reflects the overall position of a vendor within an entire market. An MQ leader tends to do well at a broad selection of products/services within that market, but is not necessarily the best at any particular product/service within that market. And even the vendor who is typically best at something might not be the right vendor for you, especially if your profile or use case deviates significantly from the “typical”.

I recognize, of course, that one of the reasons that people look at visual tools like the MQ is that they want to rapidly cull down the number of vendors in the market, in order to make a short-list. I’m not naive about the fact that users will say things like, “We will only use Leaders” or “We won’t use a Niche Player”. However, this is explicitly what the MQ is not designed to do. It’s incredibly important to match your needs to what a vendor is good at, and you have to read the text of the MQ in order to understand that. Also, there may be vendors who are too small or too need-specific to have qualified to be on the MQ, who shouldn’t be overlooked.

Also, an MQ reflects only a tiny percentage of what an analyst actually knows about the vendor. Its beauty is that it reduces a ton of quantified specific ratings (nearly 5 dozen, in the case of my upcoming MQ) to a point on a graph, and a pile of qualitative data to somewhere between six and ten one-or-two-sentence bullet points about a vendor. It’s convenient reference material that’s produced by an exhaustive (and exhausting) process, but it’s not necessarily the best medium for expressing an analyst’s nuanced opinions about a vendor.

I say this in advance of the Web hosting MQ’s release: In general, the greater the breadth of your needs, or the more mainstream they are, the more likely it is that an MQ’s ratings are going to reflect your evaluation of the vendors. Vendors who specialize in just a single use case, like most of the emerging cloud vendors, have market placements that reflect that specialization, although they may serve that specific use case better than vendors who have broader product portfolios.

What makes for an effective MQ briefing?

My colleague Ted Chamberlin and I are currently finalizing the new Gartner Magic Quadrant for Web Hosting. This year, we’ve nearly doubled the number of providers on the MQ, adding a bunch of cloud providers who offer hosting services (i.e., providers who are cloud system infrastructure service providers, and who aren’t pure storage or backup).

The draft has gone out for vendor review, and these last few days have been occupied by more than a dozen conversations with vendors about where they’ve placed in the MQ. (No matter what, most vendors are convinced they should be further right and further up.) Over the course of these conversations, one clear pattern seems to be characterizing this year: We’re seeing lots of data presented in the feedback process that wasn’t presented as part of the MQ briefing or any previous briefing the vendor did with us.

I recognize the MQ can be a mysterious process to vendors. So here’s a couple of thoughts from the analyst side on what makes for effective MQ briefing content. These are by no means universal opinions, but may be shared by my colleagues who cover service businesses.

In brief, the execution axis is about what you’re doing now. The vision axis is about where you’re going. A set of definitions for the criteria on each axis are included with every vendor notification that begins the Magic Quadrant process. If you’re a vendor being considered for an MQ, you really want to read the criteria. We do not throw darts to determine vendor placement. Every vendor gets a numerical rating on every single one of those criteria, and a tool plots the dots. It’s a good idea to address each of those criteria in your briefing (or supplemental material, if you can’t fit in everything you need into the briefing).

We generally have reasonably good visibility into execution from our client base, but the less market presence you have, especially among Gartner’s typical client base (mid-size business to large enterprise, and tech companies), the less we’ve probably seen you in deals or have gotten feedback from your customers. Similarly, if you don’t have much in the way of a channel, there’s less of a chance any of your partners have talked to us about what they’re doing with you. Thus, your best use of briefing time for an MQ is to fill us in on what we don’t know about your company’s achievements — the things that aren’t readily culled from publicly-available information or talking to prospects, customers, and partners.

It’s useful to briefly summarize your company’s achievements over the last year — revenue growth, metrics showing improvements in various parts of the business, new product introductions, interesting customer wins, and so forth. Focus on the key trends of your business. Tell us what strategic initiatives you’ve undertaken and the ways they’ve contributed to your business. You can use this to help give us context to the things we’ve observed about you. We may, for instance, have observed that your customer service seems to have improved, but not know what specific measures you took to improve it. Telling us also helps us to judge how far along the curve you are with an initiative, which in turn helps us to advise our clients better and more accurately rate you.

Vision, on the other hand, is something that only you can really tell us about. Because this is where you’re going, rather than where you are now or where you’ve been, the amount of information you’re willing to disclose is likely to directly correlate to our judgement of your vision. A one-year, quarter-by-quarter roadmap is usually the best way to show us what you’re thinking; a two-year roadmap is even better. (Note that we do rate track record, so you don’t want to claim things that you aren’t going to deliver — you’ll essentially take a penalty next year if you failed to deliver on the roadmap.) We want to know what you think of the market and your place in it, but the very best way to demonstrate that you’re planning to do something exciting and different is to tell us what you’re expecting to do. (We can keep the specifics under NDA, although the more we can talk about publicly, the more we can tell our clients that if they choose you, there’ll be some really cool stuff you’ll be doing for them soon.) If you don’t disclose your initiatives, we’re forced to guess based on your general statements of direction, and generally we’re going to be conservative in our guesses, which probably means a lower rating than you might otherwise have been able to get.

The key thing to remember, though, is that if at all possible, an MQ briefing should be a summary and refresher, not an attempt to cram a year’s worth of information into an hour. If you’ve been doing routine briefings covering product updates and the launch of key initiatives, you can skip all that in an MQ briefing, and focus on presenting the metrics and key achievements that show what you’ve done, and the roadmap that shows where you’re going. Note that you don’t have to be a client in order to conduct briefings. If MQ placement or analyst recommendations are important to your business, keep in mind that when you keep an analyst well-informed, you reap the benefit the whole year ’round in the hundreds or even thousands of conversations analysts have with your prospective customers, not just on the MQ itself.

Wading into the waters of cloud adoption

I’ve been pondering the dot write-ups that I need to do for Gartner’s upcoming Cloud Computing hype cycle, as well as my forthcoming Magic Quadrant on Web Hosting (which now includes a bunch of cloud-based providers), and contemplating this thought:

We are at the start of an adoption curve for cloud computing. Getting from here, to the realization of the grand vision, will be, for most organizations, a series of steps into the water, and not a grand leap.

Start-ups have it easy; by starting with a greenfield build, they can choose from the very beginning to embrace new technologies and methodologies. Established organizations can sometimes do this with new projects, but still have heavy constraints imposed by the legacy environment. And new projects, especially now, are massively dwarfed by the existing installed base of business IT infrastructure: existing policies (and regulations), processes, methodologies, employees, and, of course, systems and applications.

The weight of all that history creates, in many organizations, a “can’t do” attitude. Sometimes that attitude comes right from the top of the business or from the CIO, but I’ve also encountered many a CIO eager to embrace innovation, only to be stymied by the morass of his organization’s IT legacy. Part of the fascination of the cloud services, of course, is that it allows business leaders to “go rogue” — to bypass the IT organization entirely in order to get what they want done ASAP, without much in the way of constraints and oversight. The counter-force is the move to develop private clouds that provide greater agility to internal IT.

Two client questions have been particularly prominent in the inquiries I’ve been taking on cloud (a super-hot topic of inquiry, as you’d expect): Is this cloud stuff real? and What can I do with the cloud right now? Companies are sticking their toes into the water, but few are jumping off the high dive. What interests me, though, is that many are engaging in active vendor discussions about taking the plunge, even if their actual expectation (or intent) is to just wade out a little. Everyone is afraid of sharks; it’s viewed as a high-risk activity.

In my research work, I have been, like the other analysts who do core cloud work here at Gartner, looking at a lot of big-picture stuff. But I’ve been focusing my written research very heavily on the practicalities of immediate-term adoption — answering the huge client demand for frameworks to use in formulating and executing on near-term cloud infrastructure plans, and in long-term strategic planning for their data centers. The interest is undoubtedly there. There’s just a gap between the solutions that people want to adopt, and the solutions that actually exist in the market. The market is evolving with tremendous rapidity, though, so not being able to find the solution you want today doesn’t mean that you won’t be able to get it next year.

Vendor horror stories

Everyone has vendor horror stories. No matter how good a vendor normally is, there will be times that they screw up. Some customers will exacerbate a vendor’s tendency to screw up — for instance, they may be someone the vendor really shouldn’t have tried to serve in the first place (heavy customization, i.e., many one-offs from a vendor who emphasizes standardization), or they may just be unlucky and have a sub-par employee on their account team.

Competitors of a vendor, especially small, less-well-known ones, will often loudly trumpet, as part of a briefing, how they won such-and-such a customer from some more prominent vendor, and how that vendor did something particularly horrible to that customer. I often find myself annoyed at such stories. It’s fine to say that you frequently win business away from X company. It’s great to explain your points of differentiation from your rivals. I’m deeply interested in who you think your most significant competitors are. But it’s declasse’ to tell me how much your competitors suck. Also, I can often hear the horror-story anomalies in those tales, as well as detect the real reason — like the desire to shift from a lightly-managed environment to a entirely managed one, or the desire to go from managed to nearly entirely self-managed, etc. I’ll often ask a vendor point-blank about that, and get an admission that this was what really drove the sale. So why not be honest about that in the first place? Say something positive about what you do well.

I think, for the most part, that it doesn’t work on prospective customers any better than it works on analysts. Most decent people recoil somewhat at hearing others put down, whether they are individuals or competing vendors. Prospects often ask me about badmouthing; naturally, they wonder what’s behind the horror stories, but they also wonder why the vendor feels the need to badmouth a competitor in the first place.

I often find that it’s not really the massive, boneheaded incidences that tend to drive churn, anyway. They can be the flash point that precipitates a departure, but far more often, churn is the result of the accumulation of a pile of things that the customer perceives as slights. The vendor has failed to generate competence and/or caring. While sincerity is not a substitute for competence, it can be a temporary salve for it; conversely, competence without conveying that the customer is valued can also be negatively perceived. Human beings, it seems, like to feel important.

Horror stories can be useful to illustrate these patterns of weakness for a particular vendor — a vendor that has trouble planning ahead, a vendor whose proposed customer architectures have a tendency not to scale well, a vendor with a broken service delivery structure, a vendor that doesn’t take accountability, and so on. Interestingly, above-and-beyond stories about vendors can cut both ways — they can illustrate service that is consistently good but is sometimes outstanding, but they can also illustrate exceptions to a vendor’s normal pattern of mediocre service.

As an analyst, I tend to pay the most attention to what customers say about their routine interactions with the vendor. Crisis management is also an important vendor skill, and I like to know how well a vendor responds in a crisis; similarly, the ramp up to getting a renewal is also an important skill. However, it’s the day-to-day stuff that tends to most color people’s perceptions of the relationship.

Still, we all like to tell stories. I’m always looking for a good case study, especially one that illustrates the things that went wrong as well as the things that went right.

Link round-up

Recent links of interest…

I’ve heard that no less than four memcached start-ups have been recently funded. GigaOM speculates interestingly on whether memcached is good or bad for MySQL. It seems to me that in the age of cloud and hyperscale, we’re willing to sacrifice ACID compliance in many our transactions. RAM is cheap, and simplicity and speed are king. But I’m not sure that the widespread use of memcached in Web 2.0 applications, as a method of scaling a database, reflects the strengths of memcache so much as they reflect the weaknesses of the underlying databases.

Column-oriented databases are picking up some buzz lately. Sybase has a new white paper out on high-performance analytics. MySQL is plugging Infobright, a column-oriented engine for MySQL (replacing MyISAM, InnoDB, etc., just like any other engine).

Brian Krebs, the security blogger for the Washington Post, has an excellent post called The Scrap Value of a Hacked PC. It’s an examination of the ways that hacked PCs can be put to criminal use, and it’s intended to be printed out and handed to end-users who don’t think that security is their personal responsibility.

My colleague Ray Valdes has some thoughts on intuition-based vs. evidence-based design. It’s a riff on the recent New York Times article, Data, Not Design, Is King in the Age of Google, and a departing designer’s blog post that provides a fascinating look at data-driven decision making in an environment where you can immediately test everything.

Google and Salesforce.com

While I’ve been out of the office, Google has made some significant announcements. My colleague Ray Valdes has been writing about Google Wave and its secret sauce. I highly encourage you to go read his blog.

Google and Salesforce.com continue to build on their partnership. In April, they unveiled Salesforce for Google Apps. Now, they’re introducing Force.com for Google App Engine.

The announcement, in a nutshell, is this: There are now public Salesforce APIs that can be downloaded, and will work on Google App Engine (GAE). Those APIs are a subset of the functionality available in Force.com’s regular Web Services APIs. Check out the User Guide for details.

Note that this is not a replacement for Force.com and its (proprietary) Apex programming language. Salesforce clearly articulates web services vs. Force.com in its developer guide. Rather, this should be thought of as easing the curve for developers who want to extend their Web applications for use with Salesforce data.

A question that lingers in my mind: Normally, on Force.com, a Developer Edition account means that you can’t affect your organization’s live data. If a similar restriction exists on the GAE version of the APIs, it’s not mentioned in the documentation. I wonder if you can do very lightweight apps, using live data, with just a Developer Edition account with Salesforce, if you do it through GAE. If so, that would certainly open up the realm of developers who might try building something on the platform.

My colleague Eric Knipp has also blogged about the announcement. I’d encourage you to read his analysis.

What’s the worth of six guys in a garage?

The cloud industry is young. Amazon’s EC2 service dates back just to October 2007, and just about everything related to public cloud infrastructure post-dates that point. Your typical cloud start-up is at most 18 months old, and in most cases, less than a year old. It has a handful of developers, some interesting tech, plenty of big dreams, and the need for capital.

So what’s that worth? Do you buy their software, or do you hire six guys, put them in nice offices, and give them a couple of months to try to duplicate that functionality? Do you just go acquire the company on the cheap, giving six guys a reasonably nice payday for the year of their life spent developing the tech, and getting six smart employees to continue developing this stuff for you? How important is time to market? And if you’re an investor, what type of valuation do you put on that?

Infrastructure and systems management is fairly well understood. Although the cloud is bringing some new ideas and approaches, people need most of the same stuff on the cloud that they’ve traditionally needed in the physical world. That means the near-term feature roadmaps are relatively clear-cut, and it’s a question of how many developers you can throw at cranking out features as quickly as possible. Some approaches have greater value than others, and there’s inherent value in well-developed software, but the question is, what is the defensible intellectual property? Relatively few companies in this space have patentable technology, for instance.

The recent Oracle acquisition of Virtual Iron may pose one possible answer to this. One could say the same about the Cincinnatti Bell (CBTS) acquisition of Virtual Blocks back in February. The rumor mill seems to indicate that in both cases, the valuations were rather low.

Don’t get me wrong. There are certainly companies out there who are carving out defensible spaces and which have exciting, interesting, unique ideas backed by serious management and technical chops. But as with all such gold rushes to majorly hyped tech trends, there’s also a lot of me-toos. What intrigues me is the extent to which second-rate software companies are getting funding, but first-rate infrastructure services companies are not.

The cloud computing forecast

John Treadway of Cloud Bzz asked my colleague Ben Pring, at our Outsourcing Summit, about how we derived our cloud forecast. Ben’s answer is apparently causing a bit of concern. I figured it might be useful for me to respond publicly, since I’m one of the authors of the forecast.

The full forecast document (clients only, sorry) contains a lot of different segments, which in turn make up the full market that we’ve termed “cloud computing”. We’ve forecasted each segment, along with subsegments within them. Those segments, and their subsegments, are Business Process Services (cloud-based advertising, e-commerce, HR, payments, and other); Applications (no subcategories; this is “cloud SaaS”); Application Infrastructure (platform and integration); and System Infrastructure (compute, storage, and backup).

Obviously, one argue whether or not it’s valid to include advertising revenue, but a key point that should not be missed is that in the trend towards the consumerization of IT, it is the advertiser that often implicitly pays for the consumer’s use of an IT service, rather than the consuer himself. Advertising revenue is a significant component of the overall market, part of the “cloud” phenomenon even if you don’t necessarily think of it as “computing”.

Because we offer highly granular breakouts within the forecast, those who are looking for specific details or who wish to classify the market in a particular way should be able to do so. If you want to define cloud computing as just typical notions of PaaS plus IaaS, for instance, you can probably simply take our platform, compute, and storage line-items and add them together.

Is it confusing to see the giant number with advertising included? It can be. I often start off descriptions of our forecast with, “This is a huge number, but you should note that a substantial percentage of these revenues are derived from online advertising.” and then drill down into a forecast for a particular segment or subsegment of audience interest.

Giant numbers can be splashily exciting on conference presentations, but pretty much anyone doing anything practical with the forecast (like trying to figure out their market opportunity) looks at a segment or even a subsegment.

The perils of defaults

A Fortune 1000 technology vendor installed a new IP phone system last year. There was one problem: By IT department policy, that company does not change any defaults associated with hardware or software purchased from a vendor. In this case, the IP phones defaulted to no ring tone. So the phone does not ring audibly when it gets a call. You can imagine just how useful that is. Stunningly, this remains the case months after the initial installation — the company would rather, say, miss customer calls, than change the Holy Defaults.

A software vendor was having an interesting difficulty with a larger customer. The vendor’s configuration file, as shipped with the software, has defaults set up for single-server operation. If you want to run multi-server for high availability or load distribution, you need to change some of the defaults in the configuration file. They encountered a customer with the same kind of “we do not change any defaults”. Unsurprisingly, their multi-server deployment was breaking. The vendor’s support explained what was wrong, explained how to fix it, and was confounded by the policy. This is one of the things a custom distribution from the vendor can be used for, of course, but it’s a head-slapping moment and a grotesque waste of everyone’s time.

Now I’m seeing cloud configurations confounding people who have these kinds of policies. What is “default” when you’re picking from drop-down menus? What do you do when the default selection is something other than what you actually need? And the big one: Will running software on cloud infrastructure necessitate violating virgin defaults?

As an analyst, I’m used to delivering carefully nuanced advice based on individual company situations, policies, and needs. But here’s one no-exceptions opinion: “We never ever change vendor defaults” is a universally stupid policy. It is particularly staggeringly dumb in the cloud world, where generally, if you can pick a configuration, it is a supported configuration. And bluntly, in the non-cloud world, configurable parameters are also just that — things that the vendor intends for you to be able to change. There are obviously ways to screw up your configuration, but those parameters are changeable for a reason. Moreover, if you are just using cloud infrastructure but regular software, you should expect that you may need to tune configuration parameters in order to get optimal performance on a shared virtualized environment that your users are accessing remotely (and you may want to change the security parameters, too).

Vendors: Be aware that some companies, even really big successful companies, sometimes have nonsensical, highly rigid policies regarding defaults. Consider the tradeoffs between defaults as a minimalistic set, and defaults as a common-configuration set. Consider offering multiple default “profiles”. Packaging up your software specifically for cloud deployment isn’t a bad idea, either (i.e., “virtual appliances”).

IT management: Your staff really isn’t so stupid that they’re not able to change any defaults without incurring catastrophic risks. If they are, it’s time for some different engineers, not needlessly ironclad policies.

Out clauses

I’m seeing an increasing number of IT buyers try to negotiate “out clauses” in their contracts — clauses that let them arbitrarily terminate their services, or which allow them to do so based on certain economy-related business conditions.

People are doing this because they’re afraid of the future. If, for instance, they launch a service and it fails, they don’t want to be stuck in a two-year contract for hosting that service (or colocating that service, or having CDN services for it, etc.). Similarly, if the condition of their business deteriorates, they have an eye on what they can cut in that event.

We’re not talking about businesses that are already on the chopping block — we’re talking about businesses that seem to currently be in good health, whose prospects for growth would seem good. (Businesses that are on the chopping block, or wavering dangerously near it, are behaving in different defensive ways.)

Providers who would previously have never agreed to such conditions are sometimes now willing to negotiate clauses that address these specific fears of businesses. But don’t expect to see such clauses to be common, especially if the service provider has an up-front capital expenditure (such as equipment for dedicated, non-utility hosting). If you’re trying to negotiate a clause like this, you’re much more likely to have success if you tie it to specific business outcomes that would result in you entirely shutting down whatever it is that you’re outsourcing, rather than trying to negotiate an arbitrary out.