Blog Archives

What does the cloud mean to you?

My Magic Quadrant for Cloud Infrastructure as a Service and Web Hosting is done. The last week has been spent in discussion with service providers over their positioning and the positioning of their competitors and the whys and wherefores and whatnots. That has proven to be remarkably interesting this year, because it’s been full of angry indignation by providers claiming diametrically opposed things about the market.

Gartner gathers its data about what people want in two ways — from primary research surveys, and, often more importantly, from client inquiry, the IT organizations who are actually planning to buy things or better yet are actually buying things. I currently see a very large number of data points — a dozen or more conversations of this sort a day, much of it focused on buying cloud IaaS.

And so when a provider tells me, “Nobody in the market wants to buy X!”, I generally have a good base from which to judge whether or not that’s true, particularly since I’ve got an entire team of colleagues here looking at cloud stuff. It’s never that those customers don’t exist; it’s that the provider’s positioning has essentially guaranteed that they don’t see the deals outside their tunnel vision service.

The top common fallacy, overwhelmingly, is that enterprises don’t want to buy from Amazon. I’ve blogged previously about how wrong this is, but at some point in the future, I’m going to have to devote a post (or even a research note) to why this is one of the single greatest, and most dangerous, delusions, that a cloud provider can have. If you offer cloud IaaS, or heck, you’re a data-center-related business, and you think you don’t compete with Amazon, you are almost certainly wrong. Yes, even if your customers are purely enterprise — especially if your customers are large enterprises.

The fact of the matter is that the people out there are looking at different slices of cloud IaaS, but they are still slices of the same market. This requires enough examination that I’m actually going to write a research note instead of just blogging about it, but in summary, my thinking goes like this (crudely segmented, saving the refined thinking for a research note):

There are customers who want self-managed IaaS. They are confident and comfortable managing their infrastructure on their own. They want someone to provide them with the closest thing they can get to bare metal, good tools to control things (or an API they can use to write their own tools), and then they’ll make decisions about what they’re comfortable trusting to this environment.

There are customers who want lightly-managed IaaS, which I often think of as “give me raw infrastructure, but don’t let me get hacked” — which is to say, OS management (specifically patch management) and managed security. They’re happy managing their own applications, but would like someone to do all the duties they typically entrust to their junior sysadmins.

There are customers who want complex management, who really want soup-to-nuts operations, possibly also including application management.

And then in each of these segments, you can divide customers into those with a single application (which may have multiple components and be highly complex, potentially), and those who have a whole range of stuff that encompass more general data center needs. That drives different customer behaviors and different service requirements.

Claiming that there’s no “real” enterprise market for self-managed is just as delusional as claiming there’s no market for complex management. They’re different use cases in the same market, and customers often start out confused about where they fall along this spectrum, and many customers will eventually need solutions all along this spectrum.

Now, there’s absolutely an argument to be made that the self-managed and lightly-managed segments together represent an especially important segment of the market, where a high degree of innovation is taking place. It means that I’m writing some targeted research — selection notes, a Critical Capabilities rating of individual services, probably a Magic Quadrant that focuses specifically on this next year. But the whole spectrum is part of the cloud IaaS adoption phenomenon, and any individual segment isn’t representative of the total market evolution.

And so it begins

We’re about to start the process for the next Magic Quadrant for Cloud Infrastructure Services and Web Hosting, along with the Critical Capabilities for Cloud Infrastructure Services (titles tentative and very much subject to change). Our hope is to publish in late July. These documents are typically a multi-month ordeal of vendor cat-herding; the evaluations themselves tend to be pretty quick, but getting all the briefings scheduled, references called, and paperwork done tends to eat up an inordinate amount of time. (This time, I’ve begged one of our admin assistants for help.)

What’s the difference? The MQ positions vendors in an overall broad market. CC, on the other hand, rates individual vendor products on how well they meet the requirements for a set of defined use cases. You get use-case by use-case ratings, which means that this year we’ll be doing things like “how well do these specific self-managed cloud offerings support a particular type of test-and-development environment need”. The MQ tends to favor vendors who do a broad set of things well; a CC rating, on the other hand, is essentially a narrow, specific evaluation based on specific requirements, and a product’s current ability to meet those needs (and therefore tends to favor vendors that have great product features).

Also, we’ve decided the CC note is going to be strictly focused on self-managed cloud — Amazon EC2 and its competitors, Terremark Enterprise Cloud and its competitors, and so on. This is a fairly pure features-and-functionality thing, in other words.

Anyone thinking about participation should check out my past posts on Magic Quadrants.

Magic Quadrant (hosting and cloud), published!

The new Magic Quadrant for Web Hosting and Hosted Cloud System Infrastructure Services (On Demand) has been published. (Gartner clients only, although I imagine public copies will become available soon as vendors buy reprints.) Inclusion criteria was set primarily by revenue; if you’re wondering why your favorite vendor wasn’t included, it was probably because they didn’t, at the January cut-off date, have a cloud compute service, or didn’t have enough revenue to meet the bar. Also, take note that this is direct services only (thus the somewhat convoluted construction of the title); it does not include vendors with enabling technology like Enomaly, or overlaid services like RightScale.

It marks the first time we’ve done a formal vendor rating of many of the cloud system infrastructure service providers. We do so in the context of the Web hosting market, though, which means that the providers are evaluated on the full breadth of the five most common hosting use cases that Gartner clients have. Self-managed hosting (including “virtual data center” hosting of the Amazon EC2, GoGrid, Terremark Enterprise Cloud, etc. sort) is just one of those use cases. (The primary cloud infrastructure use case not in this evaluation is batch-oriented processing, like scientific computing.)

We mingled Web hosting and cloud infrastructure on the same vendor rating because one of the primary use cases for cloud infrastructure is for the hosting of Web applications and content. For more details on this, see my blog post about how customers buy solutions to business needs, not technology. (You might also want to read my blog post on “enterprise class” cloud.)

We rated more than 60 individual factors for each vendor, spanning five use cases. The evaluation criteria note (Gartner clients only) gives an overview of the factors that we evaluate in the course of the MQ. The quantitative scores from the factors were rolled up into category scores, which in turn rolled up into overall vision and execution scores, which turn into the dot placement in the Quadrant. All the number crunching is done by software — analysts don’t get to arbitrarily move dots around.

To understand the Magic Quadrant methodology, I’d suggest you read the following:

- The official How Gartner Evaluates Vendors within a Market guide to Magic Quadrants

- My colleague Jim Holincheck’s blog post on Misunderstanding Magic Quadrants

- My blog post on How Not To Use a Magic Quadrant

- Analyst industry watcher SageCircle’s commentary

Some people might look at the vendors on this MQ and wonder why exciting new entrants aren’t highly rated on vision and/or execution. Simply put, many of these vendors might be superb at what they do, yet still not rate very highly in the overall market represented by the MQ, because they are good at just one of the five use cases encompassed by the MQ’s market definition, or even good at just one particular aspect of a single use case. This is not just a cloud-related rating; to excel in the market as a whole, one has to be able to offer a complete range of solutions.

Because there’s considerable interest in vendor selection for various use cases (including non-hosting use cases) that are unique to public cloud compute services, we’re also planning to publish some companion research, using a recently-introduced Gartner methodology called a Critical Capabilities note. These notes look at vendors in the context of a single product/service, broken down by use case. (Magic Quadrants, on the other hand, look at overall vendor positioning within an entire market.) The Critical Capabilities note solves one of the eternal dilemmas of looking at a MQ, which is trying to figure out which vendors are highly rated for the particular business need that you have, since, as I want to re-iterate again, a MQ niche player may be do the exact thing you need in a vastly more awesome fashion than a vendor rated a leader. Critical Capabilities notes break things down feature-by-feature.

In the meantime, for more on choosing a cloud infrastructure provider, Gartner clients should also look at some of my other notes:

- How to Select a Cloud Computing Infrastructure Provider

- Toolkit: Comparing Cloud Computing Infrastructure Providers

- Toolkit: Estimating the Cost of Cloud Infrastructure

For cloud infrastructure service providers: We may expand the number of vendors we evaluate for the Critical Capabilities note. If you’ve never briefed us before, we’d welcome you to do so now; schedule a briefing with myself, Ted Chamberlin, and Mike Spink (a brand-new colleague in Europe).

How not to use a Magic Quadrant

The Web hosting Magic Quadrant is currently in editing, the culmination of a six-month process (despite my strenuous efforts to keep it to four months). Many, many client conversations, reference calls, and vendor discussions later, we arrive at the demonstration of a constant challenge: the user tendency to misinterpret the Magic Quadrant, and the correlating vendor tendency to become obsessive about which quadrant they’re placed in.

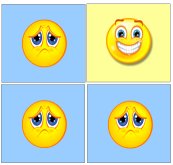

Even though Gartner has an extensive explanation of the Magic Quadrant methodology on our website, vendors and users alike tend to oversimplify what it means. So a complex methodology ends up translating down to something like this:

But the MQ isn’t intended to be used this way. Just because a vendor isn’t listed as a Leader doesn’t mean that they suck. It doesn’t mean that they don’t have enterprise clients, that those clients don’t like them, that their product sucks, that they don’t routinely beat out Leaders for business, or, most importantly, that we wouldn’t recommend them or that you shouldn’t use them.

The MQ reflects the overall position of a vendor within an entire market. An MQ leader tends to do well at a broad selection of products/services within that market, but is not necessarily the best at any particular product/service within that market. And even the vendor who is typically best at something might not be the right vendor for you, especially if your profile or use case deviates significantly from the “typical”.

I recognize, of course, that one of the reasons that people look at visual tools like the MQ is that they want to rapidly cull down the number of vendors in the market, in order to make a short-list. I’m not naive about the fact that users will say things like, “We will only use Leaders” or “We won’t use a Niche Player”. However, this is explicitly what the MQ is not designed to do. It’s incredibly important to match your needs to what a vendor is good at, and you have to read the text of the MQ in order to understand that. Also, there may be vendors who are too small or too need-specific to have qualified to be on the MQ, who shouldn’t be overlooked.

Also, an MQ reflects only a tiny percentage of what an analyst actually knows about the vendor. Its beauty is that it reduces a ton of quantified specific ratings (nearly 5 dozen, in the case of my upcoming MQ) to a point on a graph, and a pile of qualitative data to somewhere between six and ten one-or-two-sentence bullet points about a vendor. It’s convenient reference material that’s produced by an exhaustive (and exhausting) process, but it’s not necessarily the best medium for expressing an analyst’s nuanced opinions about a vendor.

I say this in advance of the Web hosting MQ’s release: In general, the greater the breadth of your needs, or the more mainstream they are, the more likely it is that an MQ’s ratings are going to reflect your evaluation of the vendors. Vendors who specialize in just a single use case, like most of the emerging cloud vendors, have market placements that reflect that specialization, although they may serve that specific use case better than vendors who have broader product portfolios.

What makes for an effective MQ briefing?

My colleague Ted Chamberlin and I are currently finalizing the new Gartner Magic Quadrant for Web Hosting. This year, we’ve nearly doubled the number of providers on the MQ, adding a bunch of cloud providers who offer hosting services (i.e., providers who are cloud system infrastructure service providers, and who aren’t pure storage or backup).

The draft has gone out for vendor review, and these last few days have been occupied by more than a dozen conversations with vendors about where they’ve placed in the MQ. (No matter what, most vendors are convinced they should be further right and further up.) Over the course of these conversations, one clear pattern seems to be characterizing this year: We’re seeing lots of data presented in the feedback process that wasn’t presented as part of the MQ briefing or any previous briefing the vendor did with us.

I recognize the MQ can be a mysterious process to vendors. So here’s a couple of thoughts from the analyst side on what makes for effective MQ briefing content. These are by no means universal opinions, but may be shared by my colleagues who cover service businesses.

In brief, the execution axis is about what you’re doing now. The vision axis is about where you’re going. A set of definitions for the criteria on each axis are included with every vendor notification that begins the Magic Quadrant process. If you’re a vendor being considered for an MQ, you really want to read the criteria. We do not throw darts to determine vendor placement. Every vendor gets a numerical rating on every single one of those criteria, and a tool plots the dots. It’s a good idea to address each of those criteria in your briefing (or supplemental material, if you can’t fit in everything you need into the briefing).

We generally have reasonably good visibility into execution from our client base, but the less market presence you have, especially among Gartner’s typical client base (mid-size business to large enterprise, and tech companies), the less we’ve probably seen you in deals or have gotten feedback from your customers. Similarly, if you don’t have much in the way of a channel, there’s less of a chance any of your partners have talked to us about what they’re doing with you. Thus, your best use of briefing time for an MQ is to fill us in on what we don’t know about your company’s achievements — the things that aren’t readily culled from publicly-available information or talking to prospects, customers, and partners.

It’s useful to briefly summarize your company’s achievements over the last year — revenue growth, metrics showing improvements in various parts of the business, new product introductions, interesting customer wins, and so forth. Focus on the key trends of your business. Tell us what strategic initiatives you’ve undertaken and the ways they’ve contributed to your business. You can use this to help give us context to the things we’ve observed about you. We may, for instance, have observed that your customer service seems to have improved, but not know what specific measures you took to improve it. Telling us also helps us to judge how far along the curve you are with an initiative, which in turn helps us to advise our clients better and more accurately rate you.

Vision, on the other hand, is something that only you can really tell us about. Because this is where you’re going, rather than where you are now or where you’ve been, the amount of information you’re willing to disclose is likely to directly correlate to our judgement of your vision. A one-year, quarter-by-quarter roadmap is usually the best way to show us what you’re thinking; a two-year roadmap is even better. (Note that we do rate track record, so you don’t want to claim things that you aren’t going to deliver — you’ll essentially take a penalty next year if you failed to deliver on the roadmap.) We want to know what you think of the market and your place in it, but the very best way to demonstrate that you’re planning to do something exciting and different is to tell us what you’re expecting to do. (We can keep the specifics under NDA, although the more we can talk about publicly, the more we can tell our clients that if they choose you, there’ll be some really cool stuff you’ll be doing for them soon.) If you don’t disclose your initiatives, we’re forced to guess based on your general statements of direction, and generally we’re going to be conservative in our guesses, which probably means a lower rating than you might otherwise have been able to get.

The key thing to remember, though, is that if at all possible, an MQ briefing should be a summary and refresher, not an attempt to cram a year’s worth of information into an hour. If you’ve been doing routine briefings covering product updates and the launch of key initiatives, you can skip all that in an MQ briefing, and focus on presenting the metrics and key achievements that show what you’ve done, and the roadmap that shows where you’re going. Note that you don’t have to be a client in order to conduct briefings. If MQ placement or analyst recommendations are important to your business, keep in mind that when you keep an analyst well-informed, you reap the benefit the whole year ’round in the hundreds or even thousands of conversations analysts have with your prospective customers, not just on the MQ itself.

Peer influence and the use of Magic Quadrants

The New Scientist has an interesting article commenting that the long tail may be less potent than previously postulated — and that peer pressure creates a winner-take-all situation.

I was jotting this blog post about Gartner clients and the target audience for the Magic Quadrant, and that article got me thinking about the social context for market research and vendor recommendations.

Gartner’s client base is primarily mid-sized business to large enterprise — our typical client is probably $100 million or more in revenue, but we also serve a lot of technology companies who are smaller than that. Beyond that subscription base, though, we also talk to people at conferences; those attendees usually represent a much more diverse set of organizations. But it’s the subscription base that we mostly talk to. (I carry an unusually high inquiry load — I’ll talk to something on the order of 700 clients this year.)

Normally, I’m interested in the comprehensive range of a vendor’s business (at least insofar as it’s relevant to my coverage). When I do an MQ, though, my subscriber base is the lens through which I evaluate companies. While I’m interested in the ways vendors service small businesses at other times, when it’s in the context of an MQ, I care only about a vendor’s relevance to our clients — i.e., the IT buyers who subscribe to Gartner services and who are reading the MQ to figure out what vendors they want to short-list.

Sometimes, when vendors think about our client base, they mistakenly assume that it’s Fortune 1000 and the largest of enterprises. While we serve those companies, we have more than 10,000 client organizations — so obviously, we serve a lot more than giant entities. The customers I talk to day after day may have a single cabinet in colocation — or fifty data centers of their own. (Sometimes both.) They might have one or two servers in managed hosting, or dozens of websites deployed via multi-dozen-server contracts. They might deliver less than a TB of content per month via a CDN, or they might be one of the largest media companies on the planet, with staggering video volumes.

These clients span an enormous range of wants and needs, but they have one significant common denominator: They are the kinds of companies that subscribe to a research and advisory firm, which means they make enough tech purchases to justify the cost of a research contract, and they have a culture which values (or at least bureaucratically mandates) seeking a neutral outside opinion.

That ideal of objectivity, however, often masks something more fundamental that ties back to the article that I mentioned: namely, the fact that many clients have an insatiable hunger to know “What are companies like mine doing?“. They are not necessarily seeking best practice, but common practice. Sometimes they seek the assurance that their non-ideal situation is not dissimilar to that of their peers at similar companies. (Although the opening line of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina — “Happy families are all alike, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” — quite possibly applies to IT departments, too.)

This is also reflected in the fact that customers often have a deep desire to talk to other customers of the same vendor, on an informal and social basis. That hunger is sometimes satisfied by online forums, but the larger the company, the more reluctant they are to discuss their business in public, although they may still share freely in a one-on-one or directly personal context.

IBM was the ultimate winner-take-all company (to use the New Scientist phrase) — the company that everyone was buying from, thus guaranteeing that you were unlikely to get fired buying IBM. Arguably, it and its brethren still are at the fat forefront of the outsourced IT infrastructure market share curve, while the bazillion hosting companies out there are spread out over the long tail. Even within the narrower confines of pure hosting, which is a highly fragmented market, and despite massive amounts of online information, peer influence has concentrated market share in the hands of relatively few vendors.

To quote the article: Which leads to a curious puzzle: why, when we have so much information at our fingertips, are we so concerned with what our peers like? Don’t we trust our own judgement? Watts thinks it is partly a cognitive problem. Far from liberating us, the proliferation of choice that modern technology has brought is overwhelming us — making us even more reliant on outside cues to determine what we like.

So I can sum up: A Magic Quadrant is an outside cue, offering expert opinion that factors in aggregated peer opinion.

Tips for a Magic Quadrant

It has been a remarkably busy December, with my client inquiries dominated by colocation calls, and it looks like the last bit of the year’s inquiries will be rounded out with last-minute year-end deals for CDN services. I’ve published what I’m going to publish this year, so I’m focusing on my first-quarter 2009 agenda, and all the preparations that go into the Magic Quadrant for Web Hosting.

We’re looking at probably double the number of providers this year than we had last year, with the high likelihood that there’s nobody at the new providers who have gone through an MQ process in some previous life. That means a certain amount of handholding, as well as an aggressive spin-up to learn providers that we don’t know well yet — providers who are entering the enterprise space but don’t necessarily have many enterprise clients yet.

I’m going to devote a certain amount of blog space over the next couple of weeks to talking about what it’s like to do an MQ, because I imagine it’s something that both IT buyers and vendors are occasionally curious about. Keep in mind that this will be personal narrative, though; what’s true for me is not necessarily true for other analysts, including my usual partner-in-crime for this particular MQ.

The quick tips for vendors:

1. Know who Gartner is advising and therefore, what our clients care about (and thus, the products and services of yours that matter to them).

2. Be able to concisely and concretely articulate what makes you different from your competitors.

3. Have a vision of the market and be able to explain how that ties into the way that you run your company and how it ties into your product plans for its future.

4. Make sure your customer references still like you.