Blog Archives

Trialing a lot of cloud IaaS providers

I’ve just finished writing the forthcoming Public Cloud IaaS Magic Quadrant (except for some anticipated tweaks when particular providers come back with answers to some questions), which has twenty providers. Although Gartner normally doesn’t do hands-on evaluations, this MQ was an exception, because the easiest way to find out if a given service can do X, was generally to get an account, and attempt to do X. Asking the vendor sometimes requires a bunch of back-and-forth, especially if they don’t do X but and are weaseling their reply, forcing you to ask a set of increasingly narrow, specific questions until you get a clear answer. Also, I did not want to constantly bombard the vendors with questions, since, come MQ time, it tends to result in a firedrill whether or not you intended the question as urgent or even particularly important. (I apologize for the fact that I ended up bombarding many vendors with questions, anyway.)

I’ve used cloud services before, of course, and I am a paying customer of two cloud IaaS providers and a hosting provider, for my personal hobbies. But there’s nothing quite like a blitzkrieg through this many providers all at once. (And I’m not quite done, because some providers without online sign-up are still getting back to me on getting a trial account.)

In the course of doing this, I have had some great experiences, some mediocre experiences, and some “you really sell this and people buy it?” experiences. I have online chatted with support folks for basic questions not covered in the documentation (like “if I stop this VM, does it stop billing me, or not?” which varies from provider to provider). I have filed numerous support tickets (for genuine issues, not for evaluation purposes). I have filed multiple bug reports. I have read documentation (sometimes scanty to non-existent). I have clicked around interfaces, and I have actually used the APIs (working in Python, and in one case, without using a library like libcloud); I have probably weirded out some vendors by doing these things at 2 am, although follow-the-sun support has been intriguing. Those of you who follow me on Twitter (@cloudpundit) have gotten little glimpses of some of these things.

Ironically, I have tried to not let these trials unduly influence my MQ evaluations, except to the extent that these things are indisputably factual — features, availability of documentation, etc. But I have taken away strong impressions about ease of use, even for just the basic task of provisioning and de-provisioning a virtual machine. There is phenomenal variation in ease of use, and many providers could really use the services of a usability expert.

Any number of these providers have made weird, seemingly boneheaded decisions in their UI or service design, for which there’s no penalty to anything in MQ scoring, but did occasionally make me stare and go, “Seriously?”

I’m reluctant to publicly call out vendors for this stuff, so I’ll pick just one example from a vendor that has open online sign-up, where it’s not a private issue that hasn’t been raised on a community forum, and they’re not the sort of vendor (I hope) to make angry calls to Gartner’s Ombudsman demanding that I take this post down. (Dear OpSource folks: Think of this as tough love, and I hope Dimension Data analyst relations doesn’t have conniptions.)

So, consider: OpSource has pre-built VMs, that come with a set amount of compute and RAM, bundled with an OS. Great. Except that you can’t alter a bundle at the time of provisioning. So, say, if I want their Ubuntu image, it comes only in a 2 CPU core config. If I want only 1 core, I have to provision that image, wait for the provision to finish, go in and edit the VM config to reduce it to 1 core, and then wait for it to restart. After I go through that song and dance once, I can clone the config… but it boggles the mind why I can’t get the config I want from the start. I’m sure there’s a good technical reason, but the provider’s job is to mask such things from the user.

The experience has also caused me to wholly revise my opinion of vCloud Director as a self-service tool for the average goomba who wants a VM. I’d always seen vCD as a demo being given by experts, where it looked like despite the pile of complex functionality, it was easy enough to use. The key thing is that the service catalogs were always pre-populated in those demos. If you’re starting from the bare vCD install that a vCloud Powered provider is going to give you, you face a daunting task. Complexity is necessary for that level of fine-grained functionality, but it’s software that is in desperate need of pre-configuration from the service provider, and quite possibly an overlay interface for Joe Average Developer.

Now we’ll see if my bank freezes my credit card for possible fraud, when I’m hit with a dozen couple-of-cents-to-a-few-dollar charges come the billing cycle — I used my personal credit card for this, not my corporate card, since Gartner doesn’t actually reimburse for this kind of work. Ironically, once I spent a bunch of time on these sites, Google and the other online ad networks have started displaying ads that consist of nothing but cloud providers, including “click here for a free trial” or “$50 credit” or whatever, but of course you can’t apply those to existing accounts, which makes every little, “hey, you’ve spent another ten cents provisioning and de-provisioning this VM” charge which I’m noting in the back of my head now, into something which will probably annoy me in aggregate come the billing cycle.

Some things, you just can’t know until you try it yourself.

What does the future of the data center look like to you?

Earlier this year, I was part of a team at Gartner that took a futuristic view of the data center, in a scenario-planning exercise. The results of that work have been published as The Future of the Data Center Market: Four Scenarios for Strategic Planning (Gartner clients only). My blog entries today are by my colleague, project leader Joe Skorupa, and provide a glimpse into this research. See the introduction for more information.

The Scenarios

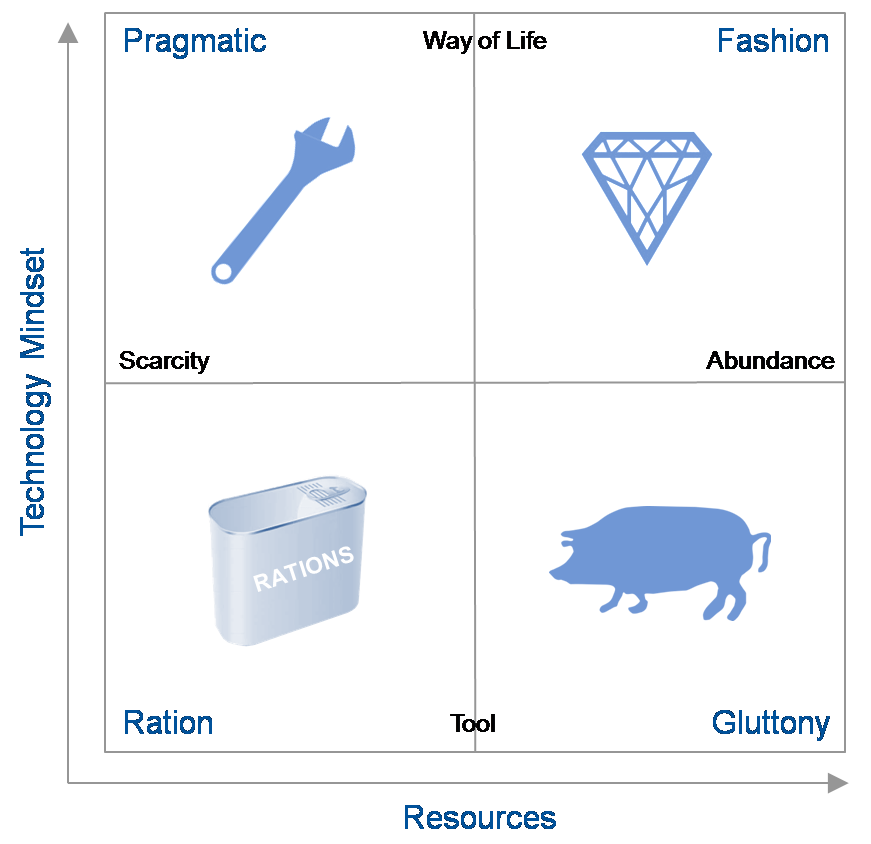

Scenarios are defined by the 4 quadrants that result from the intersection of the axes of uncertainty. In defining our scenarios we deliberately did not choose technology-related axes because they were too limiting and because larger macro forces were potentially more disruptive.

We focused on exploring how the different external factors outlined by the two axes would affect the environment into which companies would provide the products and services. Note that these external macro forces do contain technological elements.

The vertical axis describes the role and relevance of technology in the minds of the consumers and providers of technology while the horizontal axis describes availability of resources – human capital (workers with the right skill set), financial capital (investments in hardware, software, facilities or internal development) or natural resources, particularly energy — to provide IT. The resulting quadrants describe widely divergent possible futures.

- The “Tech Ration” Scenario

- This scenario describes the world in 2021 that is characterized by severely limited economic, energy, skill and technological resources needed to get the job done. People view technology as they used to think of the telephone – as a tool for a given purpose. After a decade of economic decline, wars, increasingly scarce resources and protectionist government reactions, most businesses are survival-focused.

Key Question: What would be the impact of a closed-down, localized view of the world on your strategic plans?

- The “Tech Pragmatic” Scenario

- This scenario presents a similar world of limited resources but where people are highly engaged with IT and it forms a key role in their lifestyles. Social networks and communities evolved over the decade into sources of innovation, application development and services. IT plays a major role in coordinating and orchestrating the ever-changing landscape of technology and services.

Key Question: Will your strategy be able to cope with a world of limited resources but the need for agility to meet user demands?

- The “Tech Fashion” Scenario

- This scenario continues the theme where the digital natives’ perspectives have evolved to where technology is an integral part of people’s lives. The decade preceding 2021 saw a social-media-led peace, a return to economic growth, and a flourishing of technology from citizen innovators. It is a world of largely unconstrained resources and limited government. Businesses rely on technology to maximize their opportunities. However, consumers demand the latest technology and expect it to be effective.

Key Question: How will a future where the typical IT consumer owns multiple devices and expects to access any application from every one of their devices affect your strategic planning?

- The “Tech Gluttony” Scenario

- This scenario continues in 2021 with unconstrained resources where people view technology as providing separate tools for a given purpose. Organizations developed situation-specific products and applications. Users and consumers view their technology tools as limited life one-offs. IT budgets become focused on integrating a constantly shifting landscape of tools.

Key Question: Does a world of excessive numbers of technological tools from myriad suppliers change your strategic planning?

The four scenario stories each depicts the journey to and a description of a plausible 2021 world. Of course the real future is likely to be a blend of two or more of the scenarions. To gain maximum value, you should treat each story as a history and description of the world as it is. To gain maximum benefit suspend disbelief, immerse yourself in the story, and take time to reflect on the implications for your business and enter into discussion on what plans would be most beneficial as the future unfolds.

ObPlug: Of course, Gartner analysts are available to assist in deriving specific implications for your business and formulating appropriate plans.

Introduction to the Future of the Data Center Market

Earlier this year, I was part of a team at Gartner that took a futuristic view of the data center, in a scenario-planning exercise. The results of that work have been published as The Future of the Data Center Market: Four Scenarios for Strategic Planning (Gartner clients only). My blog entries today are by my colleague, project leader Joe Skorupa, and provide a glimpse into this research.

Introduction

As a data center focused provider, how do you formulate strategic plans when the pace and breadth of change makes the future increasingly uncertain? Historical trends and incremental extrapolations may provide guidance for the next few years, but these approaches rarely account for disruptive change. Many Gartner clients that sell into the data center requested help formulating long-range strategic plans that embrace uncertainty. To assist our clients, a team of 15 Gartner from across a wide range of IT disciplines employed the scenario-based planning process to develop research about the future of the data center market. Unlike typical Gartner research, we did not focus on 12-18 month actionable advice; we focused on potential market developments/disruptions in the 2016-2021 timeframe. As a result its primary audience is C-level executives that their staffs that are responsible for long-term strategic planning. Product line managers and competitive analysts may also find this work useful.

Scenario-based planning was adopted by the US Department of Defense in the 1960s and the formal scenario-based planning framework was developed at Royal Dutch Shell in the 1970s. It has been applied to many organizations, from government entities to private companies, around the world to identify major disruptors that could impact an organization’s ability to maintain or gain competitive advantage. For this effort we used the process to identify and assess major changes in social, technological, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) environments.

These scenarios are told as stories and are not meant to be predictive and the actual future will be some subset of one or more of the stories. However, they provide a basis for deriving company-specific implications and developing a strategy to enable your company to move forward and adapt to uncertainty as the future unfolds. Exploring alternative future scenarios that are created by such major changes should lead to the discovery of potential opportunities in the market or to ensure the viability of current business models that may be critical to meeting future challenges.

To anchor the research, we focused on the following question (the Focal Issue) and its corollary:

Focal Issue: With rapidly changing end-user IT/services needs and requirements, what will be the role of the data center in 2021 and how will this affect my company’s competitiveness?

Corollary: How will the role of the data center affect the companies that sell products or services into this market?

The next post describes the scenarios themselves.

Recent research notes

This is just a quick call-out to draw your attention to the research that I’ve published recently.

- Do You Have a Business Case for a Top-Level Domain?

- I blogged previously on this topic, and this research note, done with my colleague Ray Valdes (whose coverage includes online user experience), dives deeply into consideration of the uses of gTLDs, the impact of gTLDs, the shifting landscape of how users find websites, and other things of interest to anyone considering a gTLD or preparing a business case for one.

- How to Deliver Video to Dispersed Users Without Upgrading Your Network

- Many organizations that are trying to deliver video to a lot of users think that they should use a traditional CDN. That’s not necessarily the right solution. This research note examines the range of solutions, divided by the delivery targets — Internet users outside your organization, your own employees at remote sites, Internet VPN users, and mixed-usage scenarios.

- How to Accelerate Internet Websites and Applications

- There are a range of techniques that can be used for acceleration — netwok optimization, front-end optimization (sometimes called Web content optimization or Web performance optimization), and caching — that can be delivered as appliances or services. This research note looks at selecting the right solution, and combining solutions, to maximize performance within your available budget.

(These notes are for Gartner clients only, sorry.)

Cloud IaaS coverage at Gartner

I’ve got a pair of new European colleagues, and I thought I’d take a moment to introduce, on my blog, the folks who cover public cloud infrastructure as a service here at Gartner, and to answer a common question about the way we cover the space here.

There are three groups of analysts here at Gartner who cover cloud IaaS, who belong to three different teams. Those teams are our Infrastructure and Operations (I&O) team, which is part of the division that offers advice to technology buyers (what Gartner calls “end-user organizations”) in the traditional Gartner client base of IT managers; our High-Tech and Telecom Provider (“HTTP”) division, which offers advice to vendors and investors along with end-users, and also produces quantitative market data such as forecasts and market statistics; and our IT1 division (formerly our Burton Group acquisition), which offers advice to technology implementors, generally IT architects and senior engineers in end-user organizations.

We all collaborate with one another, but these distinctions matter for anyone buying research from us. If you’re just buying what Gartner calls Core Research, you’ll have access to what the I&O analysts publish, along with anything that HTTP analysts publish into Core. To get access to HTTP-specific content, though, you’ll need to buy an upgrade, usually in the form of a Gartner for Business Laeders (GBL) research seat. The IT1 resesarch is sold separately; anything that IT1 analysts write (that’s not co-authored with analysts in other groups) goes solely to IT1 subscribers. The I&O analysts and HTTP analysts are available via inquiry by anyone who buys Gartner research, but the IT1 analysts are only inquiry-accessible by those who buy IT1 research specifically. You can, however, brief any of us — client status doesn’t matter for briefings.

So, we’re:

- Lydia Leong (HTTP, North America) – Cloud IaaS, Web hosting and colocation, content delivery networks, cloud computing and Internet infrastructure in general.

- Ted Chamberlin (I&O, North America) – Web and app hosting, colocation, cloud IaaS, network services (voice, data, and Internet).

- Drue Reeves (IT1, North America) – Data centers and cloud infrastructure, both internal and external.

- Kyle Hilgendorf (IT1, North America) – Data centers and cloud infrastructure, both internal and external.

- Tiny Haynes (I&O, Europe) – Web and app hosting, colocation, cloud IaaS, carrier services.

- Gregor Petri (HTTP, Europe) – Cloud IaaS, Web hosting and colocation, carrier services.

- Chee-Eng To (HTTP, Asia) – Carrier services in Asia, including cloud IaaS.

- Vincent Fu (HTTP, China) – Carrier services in China, including cloud IaaS.

Tiny Haynes and Gregor Petri are brand-new to Gartner, and they’ll be deepening our coverage of Europe as well as contributing to global research.

The forthcoming Public Cloud IaaS Magic Quadrant

Despite having made various blog posts and corresponded with a lot of people in email, there is persistent, ongoing confusion about our forthcoming Magic Quadrant for Public Cloud Infrastructure as a Service, which I will attempt to clear up here on my blog so I have a reference that I can point people to.

1. This is a new Magic Quadrant. We are doing this MQ in addition to, and not instead of, the Magic Quadrant for Cloud IaaS and Web Hosting (henceforth the “cloud/hosting MQ”). The cloud/hosting MQ will continue to be published at the end of each calendar year. This new MQ (henceforth the “public cloud MQ”) will be published in the middle of the year, annually. In other words, there will be two MQs each year. The two MQs will have entirely different qualification and evaluation criteria.

2. This new public cloud MQ covers a subset of the market covered by the existing cloud/hosting MQ. Please consult my cloud IaaS market segmentation to understand the segments covered. The existing MQ covers the traditional Web hosting market (with an emphasis on complex managed hosting), along with all eight of the cloud IaaS market segments, and it covers both public and private cloud. This new MQ covers multi-tenant clouds, and it has a strong emphasis on automated services, with a focus on the scale-out cloud hosting, virtual lab environment, self-managed virtual data center, and turnkey virtual data center segments. The existing MQ weights managed services very highly; by contrast, the new MQ emphasizes automation and self-service.

3. This is cloud compute IaaS only. This doesn’t rate cloud storage providers, PaaS providers, or anything else. IaaS in this case refers to the customer being able to have access to a normal guest OS. (It does not include, for instance, Microsoft Azure’s VM role.)

4. When we say “public cloud”, we mean massive multi-tenancy. That means that the service provider operates, in his data center, a pool of virtualized compute capacity in which multiple arbitrary customers will have VMs on the same physical server. The customer doesn’t have any idea who he’s sharing this pool of capacity with.

5. This includes cloud service providers only. This is an MQ for the public cloud compute IaaS providers themselves — the services focused on are ones like Amazon EC2, Terremark Enterprise Cloud, and so forth. This does not include any of the cloud-enablement vendors (no Eucalyptus, etc.), nor does it include any of the vendors in the ecosystem (no RightScale, etc.).

6. The target audience for this new MQ is still the same as the existing MQ. As Gartner analysts, we write for our client base. These are corporate IT buyers in mid-sized businesses or enterprises, or technology companies of any size (generally post-funding or post-revenue, i.e., at the stage where they’re looking for serious production infrastructure). We expect to weight the scoring heavily towards the requirements of organizations who need a dependable cloud, but we also recognize the value of commodity cloud to our audience, for certain use cases.

At this point, the initial vendor surveys for this MQ have been sent out. They have gone out to every vendor who requested one, so if you did not get one and you wanted one, please send me email. We did zero pre-qualification; if you asked, you got it. This is a data-gathering exercise, where the data will be used to determine which vendors get a formal invitation to participate in the research. We do not release the qualification criteria in advance of the formal invitations; please do not ask.

If you’re a vendor thinking of requesting a survey, please consider the above. Are you a cloud infrastructure service provider, not a cloud-building vendor or a consultancy? Is your cloud compute massively multi-tenant? Is it highly automated and focused on self-service? Do you serve enterprise customers and actively compete for enterprise deals, globally? If the answers to any of these questions are “no”, then this is not the MQ for you.

App categorization and the commodity vs. dependable cloud

At the SLA@SOI conference, my colleague Drue Reeves gave a presentation on the dependable cloud, which he defined as “a cloud service that has the availability, security, scalabilty, and risk management necessary to host enterprise applications… at a reasonable price.” We’ll be publishing research on this in the months to come, so this blog post contains relatively early-stage musings on my part.

We need enterprise-grade, dependable cloud infrastructure as as service (IaaS). But there’s also a place in the world for commodity cloud IaaS. They serve different sorts of use cases, different categories of applications. (Everything in this post refers to IaaS, but I’m just saying “cloud” for convenience.)

There are four types of applications that will move into the cloud:

- Existing enterprise applications, capable of being virtualized

- New enterprise-class applications, almost certainly Web-based

- Internet-class applications, Web 1.0 and early Web 2.0

- Global-class applications, highly sophisticated super-scalable Web 2.0 and beyond

Enterprise-class applications are generally characterized by the expectation that the underlying infrastructure is at least as reliable, performant, and secure as traditional enterprise data center infrastructure. They expect resilience at the infrastructure layer. Over the last decade, applications of this type have generally been written as three-tier, Web-based apps. Nevertheless, these apps often scale vertically rather than horizontally (scale up rather than scale out), but a very large percentage of them are small applications — ones that use a core or less of a modern CPU — and so even if they could scale out on multiple VMs, it often doesn’t make sense, from a capacity efficiency standpoint, to deploy them that way.

In the future, while an increasing percentage of new business applications will be obtained as SaaS, rather than being internally-hosted COTS apps or in-house-written apps, and more will be deployed onto business process management (BPM) suite platforms or the like, businesses will still be writing custom apps of this sort. So we will continue to need dependable infrastructure.

Moreover, many enterprise-class applications are written not just by business IT, but also by external vendors, whether ISVs, SaaS, or otherwise. Even tech companies that make their living off their websites may write enterprise-class apps. Indeed, many such apps have previously used managed hosting for the underlying infrastructure, and these companies have infrastructure dependability as an expectation.

By contrast, Internet-class applications are written to scale out. They might or might not be written to be easily distributed. They assume sufficient scale that there is an expectation that at least some things can fail without causing widespread failure, although there may still be particularly vulnerable points in the app and underlying infrstracture — the database, for instance. Resilience is generally built into the application, but these are not apps designed to withstand the Chaos Monkey.

Finally, global-class applications are written to be scale-out, highly-distributed, and to withstand massive infrastructure failures. All the resiliency is built into the application; the underlying infrastructure is assumed to be fragile. Simple underlying infrastructure components that fail cleanly and quickly (rather than dying slow deaths of degradation) are prized, because they are cheap to buy and cheap to replace; all the intelligence resides in software.

Global-class applications can use commodity cloud infrastructure, as can other use cases that do not expect a dependable cloud. Internet-class applications can also use commodity cloud infrastructure, but unless efforts are made to move more resiliency into the application layer, there are risk management issues here, and depending upon scale and needs, a dependable cloud may be preferable to commodity cloud. Enterprise-class applications need a dependable cloud.

Where resiliency resides is an architectural choice. There is no One True Way. Building resilience into the app may be the most cost-effective choice for applications which need to have “Internet scale”, but it may add unwarranted and unnecessary complexity to many other applications, making dependable infrastructure the more cost-effective choice.

Gartner research related to Amazon’s outage

In the wake of Amazon’s recent outage, we know we have Gartner clients who are interested in what we’ve written about Amazon in the past, and our existing recommendations for using cloud IaaS, and managing cloud-related risks. While we’re comfortable with our current advice, we’re also in the midst of some internal debate about what new recommendations may emerge out of this event, I’m posting a list of research notes that clients may find helpful as they sort through their thinking. This is just a reading list; it is by no means a comprehensive list of Gartner research related to Amazon or cloud IaaS. If you are a client, you may want to do your own search of the research, or ask our client services folks for help.

I will mark notes as “Core” (available to regular Gartner clients), “GBL” (available to technology and service provider clients who have subscribed to Gartner for Business Leaders or a product with similar access to research targeted at vendors), or “ITP” (available to clients of the Burton Group’s services, known as Gartner for IT Professionals post-acquisitions).

If you are specifically concerned about this particular Amazon outage and its context, and you want to read just one cautionary note, read Will Your Data Rain When the Cloud Bursts?, by my colleague Jay Heiser. It’s specifically about the risk of storage failure in the public cloud, and what you should ask your provider about their recoverability.

You might also be interested in our Cloud Computing: Infrastructure as a Service research round-up, for research related to both external cloud IaaS, and internal private clouds.

Amazon EC2

We first profiled Amazon EC2 in-depth in the November 2008 note, Is Amazon EC2 Right For You? (Core). It provides a brief overview of EC2, and examines the business case for using it, what applications are suited to using it, and the operational considerations. While some of the information is now outdated, the core questions outlined there are still valid. I am currently in the process of writing an update to this note, which will be out in a few weeks.

A deeper-dive profile can be found in the November 2009 note, Amazon EC2: Is It Ready For the Enterprise? (ITP). This goes into more technical detail (although it is also slightly out of date), and looks at it from an “enterprise readiness” standpoint, including suitability to run certain types of workloads, and a view on security and risk.

Amazon was one of the vendors profiled in our December 2010 multi-provider evaluation, Magic Quadrant for Cloud Infrastructure as a Service and Web Hosting (Core). The evaluation is focused in the context of EC2. This is the most recent competitive view of the market that we’ve published. Our thinking on some of these vendors has changed since the time it was published (and we are working on writing an update, in the form of an MQ specific to public cloud); if you are currently evaluating cloud IaaS, or any part of Amazon Web Services, we encourage you to call and place an inquiry.

Amazon S3

We did an in-depth profile for Amazon S3 in the November 2008 note, A Look at Amazon’s S3 Cloud-Computing Storage Service (Core). This note is now somewhat outdated, but please do make a client inquiry if you want to get our current thinking.

The October 2010 note, in Cloud Storage Infrastructure-as-a-Service Providers, North America (Core), provides a “who’s who” list of quick profiles of the major cloud storage providers.

An in-depth examination of cloud storage, focused on the technology and market more so than the vendors (although it does have a chart of competitive positioning), is given in the December 2010 note, Market Profile: Cloud-Storage Service Providers, 2011 (ITP).

The major cloud storage vendors are profiled in some depth in the June 2010 note, Competitive Landscape: Cloud Storage Infrastructure as a Service, North America, 2010 (GBL).

Other Amazon-Specific Things

The June 2009 note, Software on Amazon’s Elastic Compute Cloud: How to Tell Hype From Reality (Core), explores the issues of running commercial software on Amazon EC2, as well as how to separate vendor claims of Amazon partnerships from the reality of what they’re doing.

Amazon was one of the vendors who responded to the cloud rights and responsibilities published by the Gartner Global IT Council for Cloud Services. Their response, and Gartner commentary on it, can be found in Vendor Response: How Providers Address the Cloud Rights and Responsibilities (Core).

Amazon’s Elastic MapReduce service is profiled in the January 2011 note, Hadoop and MapReduce: Big Data Analytics (ITP).

Cloud IaaS, in General

A seven-part note, the top-level note of which is Evaluating Cloud Infrastructure as a Service (Core), goes into extensive detail about the range of options available in cloud IaaS provider, and how to evaluate those providers. You are highly encouraged to read it to understand the full range of market options; there’s a lot more to the market than just Amazon.

To understand the breadth of the market, and the players in particular segments, read Market Insight: Structuring the Cloud Compute IaaS Market (GBL). This is targeted at vendors ho want to understand buyer profiles and how they map to the offerings in the market.

Help with evaluating what type of data center solution is right for you can be found in the framework laid out in Data Center Sourcing: Cloud, Host, Co-Lo, or Do It Yourself (ITP).

Help with evaluating your application’s suitability for a move to the cloud can be found in Migrating Applications to the Cloud: Rehost, Refactor, Revise, Rebuild, or Replace? (ITP), which takes an in-depth look at the factors you should consider when evaluating your application portfolio in a cloud context.

Risk Management

We’ve recently produced a great deal of research related to cloud sourcing. A catalog of that research can be found in Manage Risk and Unexpected Costs During the Cloud Sourcing Revolution (Core). There’s a ton of critical advice there, especially with regard to contracting, that make these notes a must-read.

We provide a framework for evaluating cloud security and risks in Developing a Cloud Computing Security Strategy (ITP). This offers a deep dive into security and compliance issues, including how to build a cross-functional team to deal with these issues.

We take a look at assessment and auditing frameworks for cloud computing, in Determining Criteria for Cloud Security Assessment: It’s More than a Checklist (ITP). This goes deep into detail on risk assessment, assessment of provider controls, and the emerging industry standards for cloud security.

We caution about the risks of expecting that a cloud provider will have such a high level of reliability that a business continuity and recoverability are no long necessary, in Will Your Data Rain When the Cloud Bursts? (Core). This note is specifically primarily focused on data recoverability.

We provide a framework for cloud risk mitigation in Managing Availability and Performance Risks in the Cloud: Expect the Unexpected (ITP). This provides solid advice on planning your bail-out strategy, distributing your applications/data/services, and buying cyber-risk insurance.

If you are using a SaaS provider, and you’re concerned about their underlying infrastructure, we encourage you to ask them a set of Critical Questions. There are three research notes, covering Infrastructure, Security, and Recovery (all Core). These notes are somewhat old, but the questions are still valid ones.

Cloud IaaS special report

I’ve just finished curating a collection of Gartner research on cloud infrastructure as a service. The Cloud IaaS Special Report covers private and public cloud IaaS, including both compute and storage, from multiple perspectives — procurement (including contracting), governance (including chargeback, capacity, and a look at the DevOps movement), and adoption (lots of statistics and survey data of interest to vendors). Most of this research is client-only, although some of it may be available to prospects as well.

There’s a bit of free video there from my colleague David Smith. There are also links to free webinars, including one that I’m giving next week on Tuesday, March 29th: Evolve IT Strategies to Take Advantage of Cloud Infrastructure. I’ll be giving an overview of cloud IaaS going forward and how organizations should be changing their approach to IT. (If you attended my data center conference presentation, you might see that the description looks somewhat familiar, but it’s actually a totally different presentation.)

As part of the special report, you’ll also find my seven-part note, called Evaluating Cloud Infrastructure as a Service. It’s an in-depth look at the current state of cloud IaaS as you can obtain it from service providers (whether private or public) — compute, storage, networking, security, service and support, and SLAs.

Contracting in the cloud

There are plenty of cloud (or cloud-ish) companies that will sell you services on a credit card and a click-through agreement. But even when you can buy that way, it is unlikely to be maximally to your advantage to do so, if you have any volume to speak of. And if you do decide to take a contract (which might sometimes be for a zero-dollar-commit), it’s rarely to your advantage to simply agree to the vendor’s standard terms and conditions. This is just as true with the cloud as it is with any other procurement. Vendor T&Cs, whether click-through or contractual, are generally not optimal for the customer; they protect the vendor’s interests, not yours.

Do I believe that deviations from the norm hamper a cloud provider’s profitability, ability to scale, ability to innovate, and so forth? It’s potentially possible, if whatever contractual changes you’re asking for require custom engineering. But many contractual changes are simply things that protect a customer’s rights and shift risk back towards the vendor and away from the customer. And even in cases where custom engineering is necessary, there will be cloud providers who thrive on it, i.e., who find a way to allow customers to get what they need without destroying their own efficiencies. (Arguably, for instance, Salesforce.com has managed to do this with Force.com.)

But the brutal truth is also that as a customer, you don’t care about the vendor’s ability to squeeze out a bit more profit. You don’t want to negotiate a contract that’s so predatory that your success seriously hurts your vendor financially (as I’ve sometimes seen people do when negotiating with startups that badly need revenue or a big brand name to serve as a reference). But you’re not carrying out your fiduciary responsibilities unless you do try to ensure that you get the best deal that you can — which often means negotiating, and negotiating a lot.

Typical issues that customers negotiate include term of delivery of service (i.e., can this provide give you 30 days notice they’ve decided to stop offering the service and poof you’re done?), what happens in a change of control, what happens at the end of the contract (data retrieval and so on), data integrity and confidentiality, data retention, SLAs, pricing, and the conditions under which the T&Cs can change. This is by no means a comprehensive list — that’s just a start.

Yes, you can negotiate with Amazon, Google, Microsoft, etc. And even when vendors publish public pricing with specific volume discounts, customers can negotiate steeper discounts when they sign contracts.

My colleagues Alexa Bona and Frank Ridder, who are Gartner analysts who cover sourcing, have recently written a series of notes on contracting for cloud services, that I’d encourage you to check out:

- Four Risky Issues When Contracting for Cloud Services

- How to Avoid the Pitfalls of Cloud Pricing Variations

- Seven Ways to Reduce Hidden Upfront Costs of Cloud Contracts

- Six Ways to Avoid Escalating Costs During the Life of a Cloud Contract

(Sorry, above notes are clients only.)